PRINCIPLISM

Jeffrey W. Bulger. Teaching Ethics Volume 8, #1, Fall 2007. Society for Ethics Across the Curriculum. pp. 81–100.

The Belmont Report

Principlism was first formalized as a moral decision-making approach by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in a document called the Belmont Report on April 18, 1979. The Commission came into existence on July 12, 1974 when the National Research Act (Pub. L. 93-348) was signed into law. After four years of monthly deliberations, the Commission met in February 1976 for four-days at the Smithsonian Institution’s Belmont Conference Center which resulted in a statement of the basic ethical principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice, for biomedical and behavioral research. The Commission recommended that the Belmont Report be adopted in its entirety as a statement of the Department’s policy for the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare.

The Belmont Report’s cause of origin can be traced back to December 9, 1946 when the American Military Tribunal started criminal proceedings against 23 German physicians and administrators for war crimes and crimes against humanity. During the trials, the Nuremberg Code was drafted for the establishment of standards for judging individuals who conducted biomedical experiments on concentration camp prisoners. The Nuremberg Code in its final form was established in 1948 and was the first international document that advocated voluntary informed consent for participants of research on human subjects.

Although the Nuremberg Code was an international document, that advocated voluntary informed consent, it did not carry the force of law in the United States or any other country for that matter. As a result both for profit private enterprises and national governments blatantly violated the Nuremberg Code on numerous occasions. (1)

Thalidomide Case

An example of for profit private enterprise violation of informed consent is the Thalidomide Case. In the 1950’s the drug thalidomide, which was an approved sedative in Europe but not an approved sedative in the United States, was being advertised by pharmaceutical companies and prescribed by physicians for controlling sleep and nausea throughout pregnancy. Most patients that were taking this drug had not given an informed consent for this drug as they had not been informed of risks involved nor had they been informed that thalidomide had not been approved for human use by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA). In fact, the FDA actually had denied its approval six times. In Europe an estimated 8,000 to 12,000 infants were born with deformities caused by thalidomide, and of those only about 5,000 survived beyond childhood. Even though the drug did not have FDA approval 2.5 million tablets had been given to more than 1,200 American doctors and nearly 20,000 patients received thalidomide tablets, including several hundred pregnant women. In the end, 17 American children were born with thalidomide-related deformities– abnormally short limbs with toes sprouting from the hips and flipper-like arms and an estimated 40,000 people developed drug-induced peripheral neuropathy. Public outcry resulted in U.S. senate hearings passing the Kefauver Amendments into law in 1962. This law forced drug manufacturers to prove their products safety and effectiveness to the FDA before they would be allowed to bring them to market. Legislation was necessary as for profit drug companies were not going to abide by the international Nuremberg Code if money could be made and if there were no legal penalties for not abiding by international rules.

(On May 26, 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted approval for thalidomide for the treatment of leprosy with sales of $300 million per year)

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

An example of the United States government violation of informed consent is the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (1932-1972). In this case the U.S. Pubic Health Service recruited 600 low-income African-American males from Tuskegee Alabama. 400 of the men were infected with syphilis. They were told that they would be given free medical care, lunches, and transportation to and from the health care facilities each month. However, the subjects were never informed that they had the communicable disease of syphilis. As a result many of the subjects sexual encounters and wives were infected with syphilis and many of those women also gave birth to children having congenital syphilis. The cure for syphilis, a simple administration of penicillin, was readily available in the 1950’s yet the United States Government continued to keep the Tuskegee patients uninformed as to their condition, denied treatment, and/or lied to the patient by saying that they were being treated for syphilis when in reality they were only being given a placebo with no medical benefits. If by chance a subject was diagnosed as having syphilis by another physician the U.S. Government researchers would intervene to prevent treatment. In 1966, Peter Buxtun, APHS venereal disease investigator questioned the morality of the experiment by sending a letter to the director of the Division of Venereal Diseases. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) supported the Tuskegee Study and even had the support from the local chapters of the National Medical Association who represented African American physicians. After six years of unsuccessful influence Peter Buxtun decided to expose the Tuskegee Syphilis Study to the media through the Washington Star on July 25, 1972. The New York Times then published the story the next day as front page news. Because of the resultant public outcry an ad hoc advisory panel was put together and they determined that the Tuskegee Syphilis Study was medically unjustified and the study was finally stopped by the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) in 1973. The National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) filed a class action lawsuit against the study resulting in a 9 million dollar settlement and free health-care for the surviving participants and their family members who were infected with syphilis as a consequence of the government study. However, it wasn’t until May 16, 1997 that a public apology was finally given by the U.S. government to the eight remaining study subjects and their families by President Clinton. "What was done cannot be undone, but we can end the silence ... We can stop turning our heads away. We can look at you in the eye, and finally say, on behalf of the American people, what the United States government did was shameful and I am sorry."

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study was finally stopped in 1973 and as a result the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subject of Biomedical and Behavioral Research was created on July 12, 1974. After 4 years of deliberations the Commission came up with the Belmont Report as a statement of the DHEW policy on research on human subjects. This document and its principlistic approach is the genesis of what has now evolved into the moral approach of “Principlism.”

Belmont Report And Its Three Core Principles

Principlism is a moral approach based on judgments that are generally accepted by our cultural tradition and that are particularly relevant to biomedical ethics.

1. Respect for persons,

2. Beneficence, and

3. Justice.

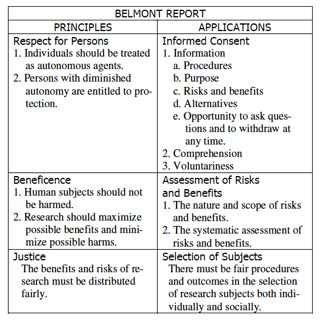

Table 1.

PRINCIPLISM: A PRACTICAL APPROACH TO

MORAL DECISION-MAKING

Principlism As A Practical Approach

Principlism has evolved into a practical approach for ethical decision-making that focuses on the common ground moral principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. The practicality of this approach is that principlism can be derived from, is consistent with, or at the very least is not in conflict with a multitude of ethical, theological, and social approaches towards moral decision-making. This pluralistic approach is essential when making moral decisions institutionally, pedagogically, and in the community as pluralistic interdisciplinary groups by definition cannot agree on particular moral theories or their epistemic justifications. However, pluralistic interdisciplinary groups can and do agree on intersubjective principles. In the development of a principlistic moral framework it is not a necessary condition that the epistemic origins and justifications of these principles be established. Rather the sufficient condition is that most individuals and societies, would agree that both prescriptively and descriptively there is wide agreement with the existence and acceptance of the general values of autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice.

Specifying and Balancing

Once these principles have been established the practical activity then becomes that of specifying how the principles are to be used in specific situations and balancing the principles with the other competing moral principles. In using this approach, every moral decision will be dilemmatic in that the agent will be to some degree either morally right and morally wrong under a single principle, and/or there will be two or more competing moral principles and the agent will not be able to completely fulfill one or more moral principles without violating or competing with one or more other moral principles. Dilemmatic decision-making is not unusual when making pluralistic social decisions. The Bill of Rights in the United States Constitution perfectly exemplifies this process. A citizen’s freedom of speech, for example, does not allow someone to yell “FIRE” in a crowded theater when there is no fire as individual Constitutional Rights and Liberties are constrained by other individual rights and liberties and therefore they must be specified for specific situations and then balanced with the other inevitable competing principles.

Principlism, presented as a formal criterion, is a description and prescription of moral decision-making with a deep and rich heritage that has yet to be formalized for pluralistic interdisciplinary groups. However, since all moral decision-making do in fact ultimately use this approach, in one form or another, moral decision making in pluralistic environments is possible as Principlism descriptively describes how people do in fact make moral decisions and prescriptively prescribes how people ought to act based on the intersubjective agreements of common morality. Instead of focusing on the epistemic differences of various philosophical and religious perspectives, Principlism focuses on the intersubjective agreements, and that is why it works so effectively in interdisciplinary pluralistic environments.

Principlism could be modified by adding or subtracting certain component principles yet practically the four principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice are broad and comprehensive enough to sufficiently cover most cases and will provide the necessary output power for making interdisciplinary moral decisions.

Incommensurable Beliefs

Even though pluralistic groups will in large part have shared universal values—Principlism, it is still clearly recognized that there is and will be incommensurable beliefs as to how the specification and balancing procedures found in the principlistic approach ought to be implemented. However, Principlism has the advantage over most other moral approaches in that Principlism emphasizes the shared interdisciplinary universal values or principles and uses them in a systematic and transparent fashion resulting in a greater shared understanding and/or compromise. Certainly, Principlism does not claim to be able to solve all moral dilemmas caused by conflicts of beliefs, yet Principlism, without a doubt, has tremendous output power for practicing interdisciplinary moral decision-making.

What follows will be an analysis of each of the major principles: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice.

PRINCIPLE OF AUTONOMY

Autonomy is a broad moral concept found in common morality. Etymologically autonomy is derived from the Greek words autos meaning self and nomos meaning rule i.e., self-rule. Although historically it was used mainly in reference to the sovereignty of a nation, in contemporary personal ethics, autonomy is used in reference to individuals as persons.

All autonomous choices must meet the following three necessary conditions:

1. Intention: The agent must intentionally make a choice.

2. Understanding: The agent must choose with substantial understanding.

3. Freedom: The agent must choose without substantial controlling influences.

The first criteria of agency or choosing intentionally is not a matter of degree, rather a person either chooses intentionally or they do not. The other two criterions of understanding and freedom are a matter of degree as it is impossible for anyone to have complete understanding or to be totally free from all controlling influences. However, choices are considered to be autonomous as long as there is an intentional choice along with substantial understanding and substantial freedom from controlling influences.

Moral principles have prima facie standing, meaning that they are moral principles that ought to be followed, yet under certain circumstances they can be overridden by other more relevant moral principles. Such moral competition or constraints need to be considered for example when an autonomous choice either endangers or causes undue burdens on oneself or society.

Autonomy as a basic principle of individual and social morality falls under the category of being a basic human right. Human rights are socially constructed concepts in that all rights claims are also obligations of others claims. In other words, whenever there is a right others always have some type of reciprocal personal or social obligation. If someone claims to have a right, but cannot assert just what the obligation of others would in fact be, then they are not talking about a right.

Rights are classified under two major categories; positive rights and negative rights.

Positive rights: when others in society have an obligation to provide something.

Negative rights: when others in society have an obligation to not interfere.

The principle of autonomy as a civil right is composed of a combination of both positive and negative rights. The autonomous criteria of intentionality and freedom from controlling influences seem to be composed of negative rights where others individually and socially have an obligation of not interfering with the free and intentional autonomous choice. The autonomous criterion of having understanding seems to be a positive right in that others individually and socially have an obligation either to provide or make accessible the information necessary for the making of a substantial informed autonomous decision.

Competence

Competence is a necessary condition for autonomy and is also a term so closely associated with autonomy that it shares the same three necessary conditions of intention, understanding and freedom.

The difference is that competence is defined as the ability to perform a task and autonomy is defined as self-rule. Another difference is that competence is a social gatekeeping function in that individuals are either considered legally competent or legally incompetent whereas autonomy is on a sliding scale. Even though there may technically be differing degrees or levels of competence—task performing abilities, adult persons are socially categorized as being competent until proven to be incompetent.

The threshold level for the determination of incompetence is based on the complexity or difficulty of the task or judgment being considered, not on the level of risk. Some easy tasks and judgments can be very risky and some very difficult tasks and judgments can have little if any risk at all. However, as the risk of a decision increases many laws have required a higher level of evidence for competence. The National Bioethics Advisory Commission, for example, has recommended a higher level of evidence for competence to consent to participate in research than to refuse participation in research.

Informed Consent

Informed Consent is generally considered a legal term that is also very closely related to autonomy and competence. There are two general meanings of informed consent:

1. Autonomous authorization, and

2. Institutional authorization.

An agent may give an informed consent by autonomously authorizing something—criteria #1 and still not fulfill the institutional—criteria #2. This is not considered a legal informed consent.

Conversely, an agent may give an informed consent by fulfilling the institutional—criteria #2 yet not give an autonomous authorization—criteria #1. This also is not considered a legal informed consent.

A legal informed consent demands that there must be both an autonomous authorization and an institutional authorization.

Regardless of whether the focus is on autonomy, competence, or informed consent, they all overlap on the necessary conditions of intentionality, understanding, and freedom.

Intentionality

When an agent intentionally consents to an action with substantial understanding and substantial freedom, then an autonomous decision has been made. How this autonomous consent is communicated to others is of three varieties:

1. Express Consent: When the autonomous agent verbally consents.

2. Implied Consent: When the autonomous agent infers through an action, e.g., lifting an arm for a shot.

3. Tacit Consent: When the autonomous agent silently or passively—by no objections, consents.

Once it is determined that an agent is able to intentionally make a choice, the next step is to determining if the other two criteria of understanding and freedom have been met.

Understanding

In most decision-making processes, it is essential that there is a certain amount of information disclosure for the purposes of understanding.

Legally and morally, professionals are obliged to disclose information using either the professional practice standard, the reasonable person standard, or the subjective standard.

1. Professional Practice Standard: This position asserts that the professional community’s customary practice determines what is the appropriate type and amount of information disclosure.

Problems:

a. Customary standards do not exist often times.

b. Inappropriate types and amounts of information disclosure could be “justified.”

c. Deemphasizes the importance of autonomous decision-making of the agent.

2. Reasonable Person Standard: This position asserts that information disclosure is based on what a hypothetical “reasonable person” would consider as “material information.”

Problems:

a. “Reasonable person” has never been carefully defined. The abstract and hypothetical character of a “reasonable person” makes it difficult to use this standard as they would have to project what a reasonable person would need to know. Informational needs may also differ from one reasonable person to another reasonable person.

b. “Material information” has never been carefully defined. If it is impossible to determine what the criteria for a “reasonable person” is then it is also impossible to determine what “material information” for a reasonable person would be.

3. Subjective Standard: This position asserts that information disclosure is based on the specific informational needs of the person involved, i.e., subjective. The subjective standard is an ideal moral standard of disclosure, because it alone acknowledges a person’s specific informational needs. However, what is “ideal” is not necessarily “practical.”

Problems:

a. Legally it would not be possible to determine if or when the subjective information requirement had been met as the requirement would be different from person to person.

b. If the agent does not know what information would be material or relevant for their deliberations then it cannot be expected that someone else should be able to figure out the information requirement for the agent.

c. Even if an agent could determine what information would be material or relevant specifically for them, it is not reasonably to expect individuals to do an exhaustive background and character analysis of each agent.

Under some conditions “full” disclosure can actually diminish an agent’s autonomy even to the point of making the agent incompetent. For example, within the health-care system, a health professional can legally proceed without consent under the following conditions:

1. Therapeutic Privilege:

a. emergency,

b. incompetency, and

c. waiver.

The therapeutic privilege can only be invoked if there is sufficient evidence to believe that disclosure would render the person incompetent to consent or to refuse treatment.

2. Therapeutic Placebos: Involves intentional deception or incomplete information disclosure.

3. Withholding information from research subjects: Incomplete disclosure should be permitted in research only if all of the following four necessary conditions are met:

a. Essential for Research

b. No Substantial Risk To Agent

c. Agent Informed of Incomplete Disclosure

d. Agent Consent.

Even when there is the proper type and amount of information disclosed to the agent there will still be large differences between how individuals understand, and process the information. There will always be problems of recollection, inferential errors, disproportionate fears of risks, false beliefs, and more.

Freedom

The third basic element of autonomy, competency and informed consent is that of substantial freedom from controlling influences. The three categories of controlling influences by people are persuasion, coercion, and manipulation.

1. Persuasion: Persuasion is being influence by reason. Reasoned argument provides factual information and logical analysis for the promotion of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice.

2. Coercion: Coercion occurs when a credible threat displaces a person’s self-directedness. Coercion, in most cases, renders even intentional and well-informed behavior nonautonomous, but may or may not still promote other moral principles such as beneficence, nonmaleficence, or justice.

3. Manipulation: Manipulation is when selected information is presented in such a way so as to influence the decision-maker to decide in a predetermined way. Manipulation, in most cases, renders even intentional and well-informed behavior nonautonomous, but may or may not still promote other moral principles such as beneficence, nonmaleficence, or justice.

PRINCIPLES OF BENEFICENCE AND

NONMALEFICENCE

Beneficence is the principle of contributing to the welfare of others. It is generally considered a positive concept of intentionally acting for the benefit of others, i.e., the maximization of benefits.

Nonmaleficence is the principle of not harming others. It is generally considered a negative concept of intentionally refraining from harmful actions, i.e., the minimization of burdens.

Although principlism does not have any hierarchical order with regards to the four principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence and justice, under close inspection it can be argued that justice, and autonomy are based on the principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence. The claim can be made that autonomy is an important principle for moral decision-making because it maximizes benefits and minimizes harms for the individual. The claim can also be made that justice is an important principle for moral decision-making because it maximizes benefits and minimizes harms for both the citizen individually and the community as a whole.

Principlism’s claim is that there are times in which a substantially autonomous agent may make a moral-decision that others do not believe maximizes benefits and minimizes harms to the individual or may compete with the maximizing and minimizing interests of other individuals or society. Depending on the context and type of decision, principlism argues that under balancing conditions, there are times in which individual autonomy will override the other competing principles and there are also times in which autonomy will be overridden by the competing principles of beneficence, nonmaleficence, and/or justice. The evaluation of the situation and conditions will determine the outcome.

The view of principlism is that autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice are intersubjectively valued in and of themselves. Although there may be strong influences and correlations between them they are distinct enough principles to warrant independent analysis. Any one principle, or combination of principles may be determined to be more important and/or relevant than any other or combination of principles. Of course the strongest moral assessment would be when all four principles are maximized by a particular decision or course of action.

The principlistic approach results in the creation of moral obligations of how an individual or society as a whole ought to act. Traditionally there are two types of moral obligations; perfect and imperfect.

A perfect obligation is when a person or society:

1. knows exactly what the action or refrainment in question is, and

2. knows exactly to whom the action is or is not to be directed towards. (e.g., Do not kill your brother.)

An imperfect obligation is when a person or society:

1. does not know exactly what the action or refrainment in question is, and

2. does not know exactly to whom it is or is not to be directed towards. (e.g., Be charitable to others.)

Although nonmaleficence is often times defined as a perfect obligation and beneficence as an imperfect obligation under closer inspection those distinctions quickly dissolve away.

It is not unusual to define beneficence and nonmaleficence as follows:

Beneficence

1. Imperfect obligation.

2. Positive requirement of action.

3. Agent need not be impartial.

4. Failure to act positively rarely results in legal punishment.

Nonmaleficence

1. Perfect obligation.

2. Negative requirement of refrainment.

3. Agent must be impartial.

4. Failure to refrain often results in legal punishment.

However, beneficence can also be:

1. a perfect obligation, such as a parent’s responsibility in providing good nutrition, clothing, shelter, and psychological support for their children, and

2. a negative requirement of refrainment, such as a parent’s responsibility in allowing children the benefit of experimenting with decision-making skills, and

3. impartial, such as a parent’s responsibility to benefit their children by being fair and impartial with them, and

4. hold someone legally accountable, such as a parent whose violation of beneficence, such as lack of nutrition to their children, results in legally intervention.

Likewise, nonmaleficence can be:

1. an imperfect obligation, such as not harming others, however that may be defined, and whoever that may be directed towards,

2. a positive requirement of action, such as making health-care available to those in need,

3. implemented partially, such as a parent not harming a particular child, and

4. legally neutral, such as an agent not being held legally accountable for maleficence such as the teasing of a sibling.

The principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence are best understood as the maximization of benefits and the minimization of burdens. However, there still are some conceptual and moral difficulties with these distinctions. One of the most interesting difficulties is the distinction between quantitative and qualitative benefits and burdens.

If there were no qualitative distinctions between benefits and burdens then it would be possible to implement a purely quantitative assessment. Under this quantitative rubric a person could just draw, for example, two columns listing benefits of a moral decision in the first column and burdens in the second column, sum up each column, and if the benefits outweigh the burdens then the person ought to go with the decision, if not then the person ought not to go with the decision.

However, if one unit of measure differs qualitatively from another unit of measure then the whole process becomes nonsense as you will be comparing apples with oranges. A humorous illustration might be as follows:

1. My spouse gives me 100 units of benefits and 13 units of burdens for a total of 87 units.

2. Pepperoni pizza gives me 10 units of benefits and 3 units of burdens for a total of 7 units

3. Therefore, I should be willing to trade my spouse for 13 pepperoni pizzas.

Humor aside, either there was an under estimation of the quantitative units of benefits, or what is more probably the case the quality of the relationship units is categorically different from that of the pizza units.

Since qualitative values are subjective, but not necessarily relative, it shows the importance of autonomy determinations of benefits and burdens. Since qualitative values are also part of social contracts such as human rights values, it also shows the importance of justice determinations of benefits and burdens.

The principles of beneficence and nonmaleficence are an integral part of moral-decision making and understanding the distinction between quantitative and qualitative measurements fortifies the need for autonomy and justice determinations.

PRINCIPLE OF JUSTICE

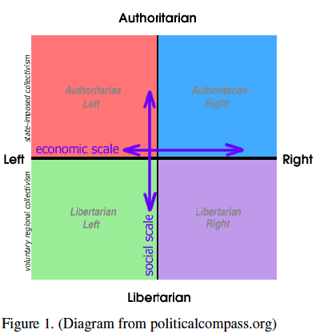

Most theories of justice can be described using various combinations and weights of the following two criteria:

1. Economic distribution: Trickle-down economics vs trickle-up economics.

2. Moral authority: Government controlled morality vs individual controlled morality.

Economic Axis

The easiest way to understand the above diagram is by thinking of the x axis and the y axis independently. The x axis is the economic line—right/left and the y axis is the social morality line—up/down.

The extreme right on the economic axis emphasizes trickle-down economics. Trickle-down economics is the viewpoint that money flows down from those who have capital wealth to the working poor. Since money flows from the top down this position holds that if there is to be any taxation then it ought not to tax capital wealth, rather it is better economically to tax the working poor, i.e., regressive taxation. Conversely, if there is to be an economic welfare system then it ought not to be for the working poor, rather welfare ought to be for the wealthy capitalists, i.e., corporate welfare.

Trickle-down economics argues for the elimination of taxation on the wealthy capitalists by the elimination of inheritance tax, capital gains tax, and dividend tax. A capital gain is the increase in value of an asset (as stock or real estate) between the time it is bought and the time it is sold. A stock dividend is the payment by a corporation of a dividend in the form of shares usually of its own stock without change in par value.

Trickle-down economics argues that you should tax the greatest amount of people the least amount of money. Since the greatest number of people in our society are the working poor, this means that society needs to focus taxation on them—regressive taxation. A regressive tax is when the burden of a tax, in proportion to the individuals overall wealth, is greater for those who make less than for those who make more. Classic examples of regressive taxation are food tax, sales tax, gas tax, and the flat tax. For example, a working poor single mother who has four teen age children will spend a much larger proportion of her total earnings at the grocery store than the wealthy capitalist. For the wealthy capitalist the food tax has little if any effect on their total wealth. Whereas for the working poor, the food tax effectively is an additional tax on a very large proportion of their total income. Trickle-down economics is the viewpoint that economic responsibility results in the maximization of regressive taxation such as food tax and sales tax, and the minimization of progressive taxes such as capital gains, dividends, and inheritance taxes.

The extreme left on the economic axis emphasizes trickle-up economics. Trickle-up economics is the viewpoint that money flows up from the working class poor to those who have capital wealth. For example, workers are paid less than the value of their labor and the extra profits then trickle-up to those who do no work other than providing capital. Since there are relatively few individuals who are making very large sums of money and they are doing so without providing any labor, other than capital, this point of view thinks that this type of economic distribution is unjust and that there needs to be a process for redistributing the wealth more justly, i.e., progressive taxation. Since money flows up from the bottom then justice demands that taxation should be greater for the few rich than on the majority of the working poor. If the goal is to keep the economy as active as possible taxation of the poor should be minimized and taxation for the capitalists should be maximized. Trickle-up economics is the viewpoint that economic responsibility results in the maximization of progressive taxation such as capital gains, dividends, and inheritance taxes, and the minimization of regressive taxes such as food tax and sales tax.

Social Morality Axis

The extreme up on the social moral axis emphasizes governmental authority with regards to social morality. This point of view maximizes governmental moral authority and minimizes the importance of personal moral autonomy. Individuals in this type of society are not respected for making autonomous moral choices through a process of fair procedures, rather individuals are forced into compliance by coercive threats and punished for noncompliance. This paternalistic point of view has little respect for personal autonomy.

The extreme down on the social moral axis emphasizes individual autonomy with regards to social morality. This point of view maximizes personal moral autonomy and minimizes paternalistic government authority. Individuals in this type of society are not forced into compliance by coercive threats and punished for noncompliance, rather their personal moral autonomy is maximized through a process of fair procedures. This antipaternalistic point of view has very high respect for personal autonomy.

Four Quadrants

The libertarian right (bottom right quadrant) emphasizes both economic and moral autonomy through the implementation of fair procedures. The focus is on the minimization of governmental authority, and the maximization of personal autonomy. This personal autonomy is maximized by the establishment of individual rights and liberties and is implemented through the process of fair procedures. As economies are determined by the process of the free-market system, they naturally tend towards trickle-down capitalistic monopolies.

The authoritarian left (top left quadrant) emphasizes both economic and moral authority of the government, usually in the form of trickle-up economics, and moral legislation. The focus is on the minimization of individual rights and liberties as implemented through the process of fair procedures, and the maximization of governmental authority. The authoritarian left is usually manifested as being totalitarian or fascist. Fascism and totalitarianism is when there is a centralized government that controls both the economy and morality of a country while suppressing opposition.

The authoritarian right (top right quadrant) emphasizes both economic and moral governmental authority, usually in the form of trickle-down economics, and moral legislation. The focus, like the authoritarian left, is on the minimization of individual rights and liberties as implemented through the process of fair procedures, and the maximization of governmental authority. The authoritarian right is also usually manifested as totalitarian or fascist to the extent that there is a centralized government that controls both the economy and morality of a country while suppressing opposition.

The libertarian left (bottom left quadrant) emphasizes both economic and moral autonomy through the implementation of fair procedures. The focus is on the minimization of governmental authority, and the maximization of personal autonomy. This personal autonomy is maximized by the establishment of individual rights and liberties and is implemented through the process of fair procedures. As economies are determined by the process of fair procedures they naturally tend towards a trickle-up egalitarian economy.

Diversity in the Compass

On any given issue a person may end up in different quadrants. However, when asked a variety of questions on a variety of subjects that relate to the economy and to social morality an average or a tally can be done and individuals can be plotted on the political compass. Then if others answer the questions as well, then a person can compare themselves with others. Historical persons can also be plotted on the political compass even if they haven’t directly answered the questions by answering the questions for them based on historical text. Although there are no units on this Cartesian graph the historical comparisons are interesting. (For more information and for a personal plotting on this graph go to policalcompass.org)

Application of Justice

The principlistic application of justice can be accomplished using a variety of social justice perspectives. Libertarians will emphasize individual moral and economic rights and liberties through a process of “fair procedures” often times independently of the determinations of benefits and burdens. Utilitarians are similar to libertarians in emphasizing individual moral and economic rights and liberties through a process of “fair procedures,” but unlike libertarians, utilitarians greatly emphasize the maximization of benefits and the minimization of burdens of both individual citizens and society as a whole. Egalitarians will emphasize equality both economically and with regards to social morality. Communitarians will emphasize the importance of culture, traditions, relationships, and casuistry and deemphasize the importance and need of individual rights and liberties.

What type or model of justice is to be emphasized will be largely dependent on the conditions and environment that the community finds itself. Types of governments ought to be determined by the history, culture, economic, diversity, and moral conditions along with the traits and abilities of its leaders and the citizens. For example a democracy would demand that its citizens be informed, competent, and tolerant of diverse points of views. To the degree that citizens lack those traits is the degree to which democracy ought not to be pursued as you may end up with the tyranny of the majority. Constitutional checks and balances along with individual rights and liberties are usually associated with most forms of democracy in order to prevent the natural tendency towards the tyranny of the majority. Communitarianism with its motto of “from each according to their ability and to each according to their need” may be the most ideal form of relationship based government but may also be one of the most practically unfulfillable with the current state of humanity and its tendency towards selfishness and being adversarial. However, morality has always been about the determining of ideal goals and objectives and striving towards that perfection along with the recognition and necessity of what does in fact practically work under the current environment that society finds itself.

Interestingly, most American citizens tend to be located in the bottom left quadrant of the political compass and most American politicians tend to be located in the top right quadrant. Republican politicians push towards the very top right quadrant and Democrat politicians are a bit more moderate but are still also in the top right quadrant. On the one hand, this is a surprising conclusion considering that most voters believe that there democratic representatives share their view of the function and role of government when in fact it turns out to be nothing further than the truth. On the other hand, perhaps this should be expected considering how corporate America demands the economic right position and many religious Americans demand an intolerant moral position towards diversity.

Conclusion

The moral approach of principlism has been briefly presented. The discussion focused on the broad general principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. Using this approach there will still be disagreements in the specification, balancing, and the coherent organization of these principles but through the process of inquiry, by multiple and diverse methods, there will be more agreement than disagreement on the resultant conclusions. Even though there are differences in epistemic justifications and beliefs between various individuals and groups within society, descriptively, there will still be wide intersubjective agreements on the general moral principles. Ideals together with practicality will help determine the specification and balancing of the principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice, and principlism will ultimately result in a morally progressive society that respects the beauty and necessity of pluralism, diversity, and moral respect.

_____

NOTES

1. See Tom L. Beauchamp, James F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics, Fifth Edition, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 81-83. Discussion on standards of disclosure.

2. Ibid. p. 88. Discussion on withholding of information and permissible deception.

3. Ibid pp. 93-98. Discussion on controlling influences.

4. Ibid p.168. Discussion on how nonmaleficence differs from beneficence.